There’s a particular kind of financial shock that tends to arrive at the worst possible moment. You’ve just lost someone. The paperwork is mounting. And then, tucked inside a letter from HMRC, comes a tax bill that nobody anticipated — sometimes for tens of thousands of pounds. All because a threshold quietly existed, and nobody in the family had ever sat down to understand it.

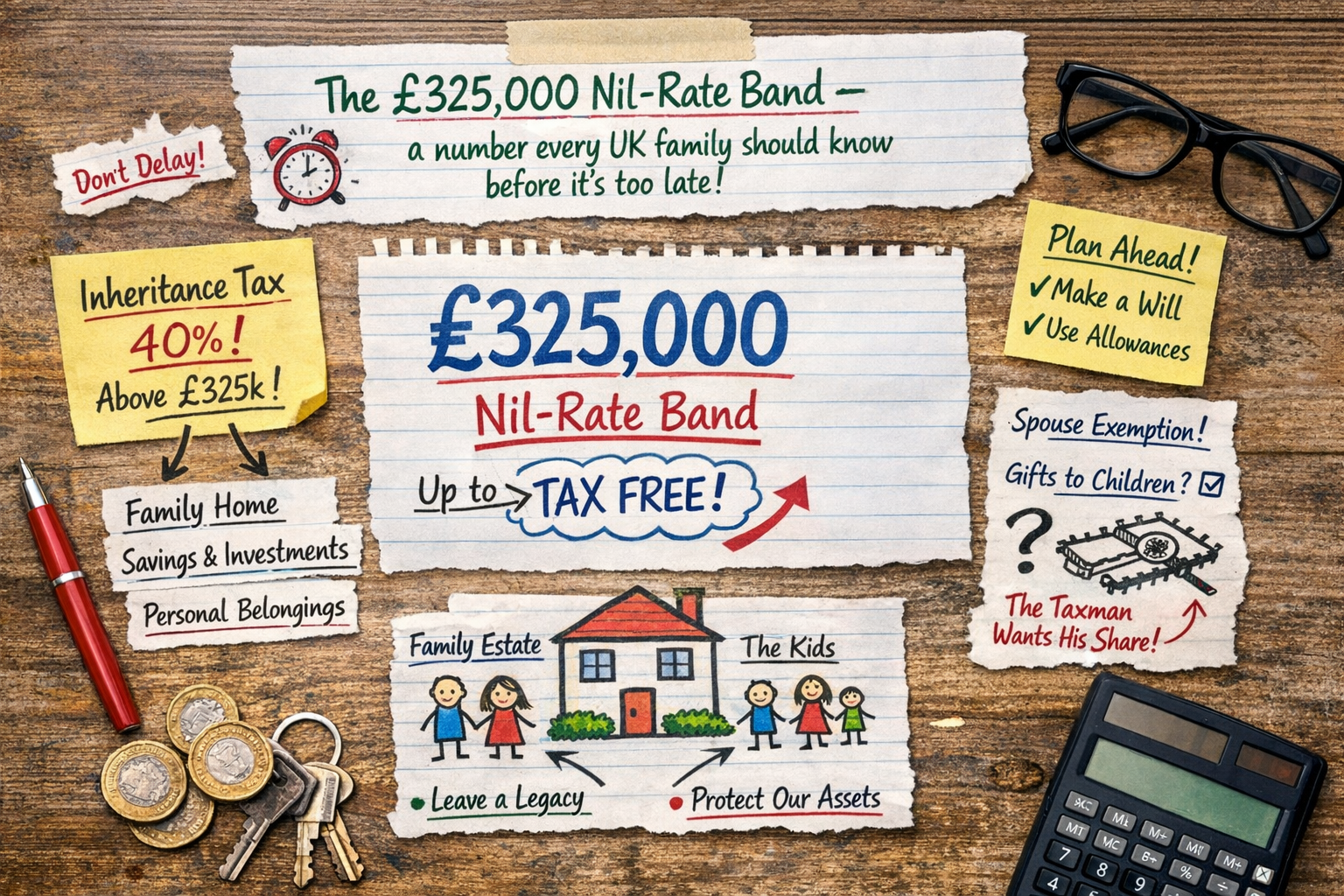

The inheritance tax limit — officially called the nil-rate band — is the single most important number in UK estate planning, and yet it’s remarkable how many people discover it only when it’s already too late to do anything clever about it. This guide is an attempt to fix that.

We’ll cover what the current thresholds actually are (including the residential one that confuses almost everyone), how spouses and civil partners can effectively double their allowance, the mechanics of the seven-year gift rule, and the situations where estates can end up paying far more than necessary simply because the planning never happened.

No jargon for jargon’s sake. Just the facts, a few worked examples, and some honest commentary on where families typically go wrong.

What the Inheritance Tax Limit Actually Means

The inheritance tax limit in the UK — formally known as the nil-rate band (NRB) — currently sits at £325,000 per person. This is the value of an estate that can pass on death completely free of inheritance tax. Everything above that threshold is taxed at 40%.

So if someone dies leaving an estate worth £525,000, inheritance tax is charged on the £200,000 above the nil-rate band. That’s £80,000 to HMRC. Not pocket change.

The 40% rate has been unchanged for years, but what has changed — and this matters enormously — is that property values across the UK have climbed dramatically while the nil-rate band has been frozen at £325,000 since 2009. The government confirmed this freeze will continue until at least 2030. The practical effect? More and more ordinary families, people who never considered themselves “wealthy,” now fall into the inheritance tax net purely because the house they bought decades ago is now worth considerably more than £325,000.

Worth knowing: HMRC collected a record £7.5 billion in inheritance tax receipts in the 2023/24 tax year — up from £5.7 billion just four years earlier. The freeze is doing exactly what freezes tend to do.

The Residential Nil-Rate Band — The Allowance Most Families Miss

Here’s where it gets more interesting — and frankly, more complicated than it should be.

Since 2017, there has been a second inheritance tax allowance specifically for homes that pass directly to descendants. This is called the Residence Nil-Rate Band (RNRB), and it’s currently worth an additional £175,000 per person.

When you stack both allowances together, a single individual can potentially pass on up to £500,000 tax-free — provided their estate includes a property left to children or grandchildren. For spouses or civil partners, that combined potential rises to £1,000,000.

That’s a meaningful number. But — and this is where the complications begin — the RNRB comes with conditions that can trip people up:

- The estate must include a residential property that the deceased once lived in (buy-to-let properties don’t count, only homes they actually occupied).

- The property must pass to a direct descendant — children, stepchildren, grandchildren. Nieces, nephews, and siblings don’t qualify.

- The allowance tapers away for estates worth more than £2 million. For every £2 over the £2m threshold, £1 of RNRB is lost. Estates above £2.35 million get nothing from it.

- If the deceased downsized or sold their home after 8 July 2015, there are specific downsizing rules that may preserve part of the allowance — but these require careful calculation.

A couple with a combined estate of £2.4 million — not unusual in parts of London and the South East — may find that the full £1 million threshold they assumed was available has significantly eroded.

Quick Reference: Current UK Inheritance Tax Allowances (2024/25)

| Allowance | Amount Per Person | Available To | Key Condition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nil-Rate Band (NRB) | £325,000 | Everyone | No conditions — applies to all estates |

| Residence Nil-Rate Band (RNRB) | £175,000 | Those leaving a home to direct descendants | Must be residential property the deceased lived in; tapers above £2m estate |

| Combined (single person) | Up to £500,000 | Individuals with qualifying property | Both bands apply |

| Combined (spouses / civil partners) | Up to £1,000,000 | Spouses/civil partners leaving to direct descendants | Transferable allowance used; estate must qualify for RNRB |

Source: HMRC — Inheritance Tax limit Overview. Rates confirmed for 2024/25 and frozen until at least April 2030.

Couples and the Transferable Allowance — How the Maths Works

Spouses and registered civil partners have a significant advantage that cohabiting partners, however long-standing, do not. When the first spouse dies, the surviving spouse can claim any unused nil-rate band from that estate. The same applies to the RNRB.

This doesn’t happen automatically — the executors of the second estate need to make a claim to HMRC — but in practice, it means a surviving spouse can potentially have double the standard inheritance tax allowances available on their death.

A simple worked example:

James and Patricia are married. James dies in 2020 leaving everything to Patricia. Because transfers between spouses escape inheritance tax limit, the estate pays no IHT and James’s full nil-rate band goes unused. Patricia’s estate now has her £325,000 NRB plus James’s unused £325,000 NRB — a combined £650,000 nil-rate band. Add both RNRB allowances (if a qualifying property is involved), and Patricia’s estate could transfer up to £1,000,000 without any IHT liability.

The transfer mechanism applies even if the first spouse died before the RNRB existed, provided the second spouse died after it came into effect. The rules also cover cases where the first spouse had a partially used NRB — in that case, only the unused proportion transfers.

One thing worth saying plainly: this is a significant piece of planning, and getting the timing wrong or failing to claim the transferred allowance has cost families dearly. The executors must submit a claim — it doesn’t happen automatically, and HMRC won’t remind you.

Gifts, the Seven-Year Rule, and the Clock That Starts Ticking

Perhaps the most misunderstood aspect of the inheritance tax limit is the way gifts interact with it. Many people assume that giving money away during their lifetime automatically removes it from their estate. Sometimes it does. Often, it doesn’t — at least not immediately.

The key concept here is the Potentially Exempt Transfer (PET). If you give money or assets to another person (other than a trust), that gift is potentially exempt — but only becomes fully exempt if you survive for seven years after making it. If you die within seven years, HMRC pulls that gift back into your estate and charges IHT on it.

Importantly, the tax on gifts doesn’t snap from zero to 40% the moment you die. There’s a sliding scale called taper relief that reduces the IHT payable on gifts made between three and seven years before death:

- 0–3 years before death: 40% (full rate)

- 3–4 years: 32%

- 4–5 years: 24%

- 5–6 years: 16%

- 6–7 years: 8%

- 7+ years: 0% (fully exempt)

Annual exemptions also sit entirely outside the seven-year rule. The annual gift exemption lets each person give away up to £3,000 per year without any IHT implications — and if you didn’t use last year’s allowance, you can carry it forward once, making a potential £6,000 in a single year. Small gifts of up to £250 per recipient per year also escape IHT, as do wedding gifts (up to set limits depending on your relationship to the couple).

Regular gifts out of surplus income — as opposed to capital — can also qualify for exemption, provided the money genuinely flows from income rather than savings, and the donor maintains their own standard of living throughout. This is one of the more powerful and underused exemptions in the IHT toolkit, but good record-keeping is essential if HMRC ever challenges it.

IHT Gift Exemptions at a Glance

| Type of Gift | Annual Limit | Notes / Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Annual exemption | £3,000 per donor | Unused amount can carry forward one year (max £6,000 in a single year) |

| Small gift exemption | £250 per recipient | Any number of recipients; cannot combine with annual exemption for same person |

| Wedding / civil partnership gift | £5,000 (parent), £2,500 (grandparent), £1,000 (others) | Gift must be made before the ceremony; no retrospective gifts |

| Gifts from income | No set limit | Must be regular, habitual, from surplus income only — good records essential |

| Potentially Exempt Transfer (PET) | Unlimited | Fully exempt only if donor survives 7 years; taper relief applies from year 3 |

For further detail, see HMRC guidance on IHT and gifts.

The Reliefs That Can Dramatically Change the Calculation

Beyond allowances for individuals and couples, certain types of assets carry their own IHT exemptions — some of them extraordinarily generous.

Business Property Relief (BPR) allows qualifying business assets to pass with either 100% or 50% relief from inheritance tax limit. Unlisted trading company shares, business interests, and certain land or buildings in active business use can all potentially attract this relief. This has historically ranked among the most valuable reliefs available, particularly for family business owners — though recent Budget announcements propose changes to BPR from April 2026 that will cap the 100% relief at £1 million, with anything above facing an effective 20% rate. These proposals are still being finalised, so do take specialist advice if business assets make up a significant part of your estate.

Agricultural Property Relief (APR) works similarly for qualifying agricultural land and farmhouses. Again, proposed changes from April 2026 will affect how this relief applies for larger agricultural estates.

Spouse/civil partner exemption is perhaps the most complete: transfers between spouses or civil partners who are both UK domiciled escape IHT entirely — whether in life or on death. This exemption carries no upper limit when both parties hold UK domicile. If one partner lacks UK domicile, the law has historically capped the available relief, though elections exist to address this.

Charity donations in a Will can reduce the IHT rate from 40% to 36% if at least 10% of the “net estate” (the taxable portion) is left to qualifying charities. For some estates, adjusting the charitable bequest to hit that 10% threshold saves more than the extra gift costs — a calculation worth running through with an adviser.

Trusts, Life Insurance, and Other Structural Moves

Trusts have a complicated reputation — some of it deserved, a lot of it not. Putting assets into a trust can take them outside your estate for IHT purposes, but the structure, setup date, and type of trust all drive the outcome. Certain trusts (called “relevant property trusts”) attract their own IHT charges every ten years and on exits, so poor planning can inadvertently generate new tax liabilities rather than reduce them.

What is straightforward — and often overlooked — is using life insurance to cover a known IHT liability. A whole-of-life policy written in trust (this part is critical — leave it out of trust, and the payout simply swells the estate and HMRC taxes it too) can deliver a tax-free lump sum to beneficiaries specifically to cover the IHT bill. The estate doesn’t grow by one penny; the insurance picks up the tab.

This doesn’t reduce the IHT owed. But it means your children don’t have to sell the family home — or wait months for a house sale to proceed — just to clear a tax bill before probate can be granted. For property-heavy estates where cash is limited, this is often the most practical solution on the table.

⚠️ The Probate Timing Problem: IHT must generally be paid before probate is granted — but you often need probate to access the assets to pay the bill. HMRC does allow instalments for certain assets (including property), but interest accrues on unpaid amounts. This circular problem catches families out more than almost anything else. Planning in advance for how the bill will actually be paid is just as important as minimising what’s owed.

What “Domicile” Has to Do With Any of This

A slightly niche but genuinely important point: UK inheritance tax applies based on domicile, not just residence. Your domicile is broadly the country you consider your permanent home — and it’s a legal concept that can be surprisingly difficult to change, even if you’ve lived abroad for years.

If you hold UK domicile, HMRC levies IHT across your entire worldwide estate. If you are non-UK domiciled, only your UK-based assets fall within its reach. Changing domicile of choice demands clear evidence of a permanent intention to settle in another country — simply moving abroad does not achieve it.

This matters particularly for families with international connections, overseas property, or foreign bank accounts. The interaction between UK IHT and equivalent taxes in other jurisdictions can be complex, and double taxation treaties don’t always provide the relief people expect.

The Three Mistakes That Cost Families the Most

After years of working through inheritance tax cases, certain errors come up with grim regularity. None of them are unusual. All of them are avoidable.

1. Assuming the house won’t trigger IHT. This was probably true in 1990. It’s demonstrably not true for millions of UK homeowners today. Run the numbers on your actual estate value — property, savings, investments, life insurance not written in trust — and then check it against the threshold. You may be surprised.

2. Giving assets away but not surviving seven years. Gifting is one of the most effective long-term planning tools available. But it requires time. Someone who gives away £300,000 and then dies fourteen months later may have inadvertently complicated their estate without saving a penny. The time to start gifting is well before it becomes urgent.

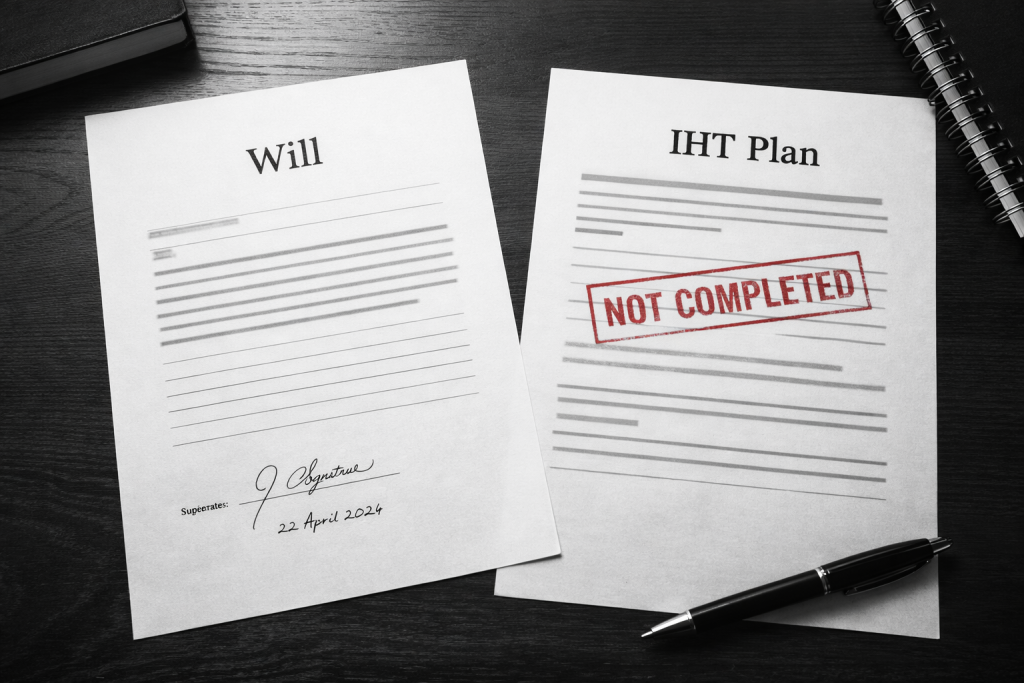

3. Treating Wills and IHT planning as the same thing. A Will tells everyone where the assets go. IHT planning determines how much of those assets the tax man takes first. They’re related but not identical. You can have an impeccably drafted Will and still hand a large proportion of the estate to HMRC because nobody addressed the planning side. Equally, solid IHT planning can unravel entirely if a stale Will then sends the assets somewhere the tax strategy never anticipated.

The firms that do this well — like Ask Accountant, whose personal tax planning and inheritance tax work sits at the intersection of both disciplines — treat the Will and the tax plan as a single coordinated strategy, not two separate documents written by two separate people who never spoke to each other.

The Inheritance Tax Landscape Is Shifting — What’s Coming

Following the Autumn Budget 2024, the inheritance tax picture in the UK is changing in ways that affect a broader population than many anticipated. Key developments that will affect planning going forward:

- Pension funds within IHT from April 2027: Currently, defined contribution pension pots sit outside the estate and pass to beneficiaries free of IHT. From April 2027 (subject to legislation), HMRC will draw unspent pension funds into the IHT calculation. This is a seismic shift for anyone treating their pension as an inheritance vehicle — and for those who haven’t planned around it, potentially a very expensive one.

- Agricultural and Business Property Relief reforms from April 2026: As noted above, the 100% relief rate will be capped at £1 million combined for APR and BPR, with a 20% effective IHT rate applying above that threshold. Family farms and business owners need to revisit their planning before this change takes effect.

- The nil-rate band freeze continues: There is no suggestion the NRB or RNRB will rise with inflation in the near term. The real value of the inheritance tax limit continues to erode.

For families with business interests, farm assets, or significant pension savings, the window for planning before these changes land is narrowing. This is genuinely a case where early action — not panic, but measured, proactive work — saves real money.

Getting the Numbers Right Before They Matter

The inheritance tax limit is, at its core, a planning problem. The rules are reasonably well-defined. The allowances exist. The reliefs are there to be used. What trips families up — consistently, expensively — is not complexity, but inertia. The conversation that never got had, the Will that was never updated, the gifts that were never started.

If you’re not sure where your estate currently sits relative to the nil-rate band — or if you haven’t reviewed your position since the Autumn Budget announcements — that review is where to start. Not with a major restructuring, not with anything irreversible. Just with clarity about the numbers.

The team at Ask Accountant, based at 178 Merton High St, London SW19 1AY, work specifically on inheritance tax planning alongside broader tax advisory and accounting services. If you want someone to walk through your current estate position and flag where there’s room to plan more efficiently, they can be reached on +44(0)20 8543 1991.

Related reading from Ask Accountant that might help at this stage:

- How to maximise your inheritance tax allowance

- Strategies for reducing IHT on family property

- Inheritance tax gift rules every family should know

- Understanding the inheritance tax threshold

- UK inheritance tax planning guide

- Inheritance tax calculator

Frequently Asked Questions About the Inheritance Tax Limit

What is the current inheritance tax limit in the UK?

The standard inheritance tax limit — or nil-rate band — is currently £325,000 per person. With the Residence Nil-Rate Band added (for those leaving a home to direct descendants), a single individual can pass up to £500,000 tax-free. For spouses or civil partners using both transferable allowances, the combined threshold can reach £1,000,000.

When does inheritance tax need to be paid?

IHT is generally due six months after the end of the month of death. So if someone dies in March, the bill is due by the end of September of the same year. Interest accrues on unpaid tax after that deadline. For assets like property, instalment payments spread over ten years are available — though interest applies to the outstanding balance throughout.

Do I have to pay inheritance tax if I inherit from my parents?

It depends on the size of the estate, not who you are as a beneficiary. The estate itself carries the IHT liability — not the individual inheritor. If the estate falls within the available nil-rate band thresholds, there is nothing to pay. If it exceeds them, the executor settles the IHT bill from the estate before distributing anything to beneficiaries. You, as an inheritor, won’t receive a personal demand from HMRC — but you may receive less than the full asset value as a result.

Does the seven-year rule apply to all gifts?

Most outright gifts to individuals (called Potentially Exempt Transfers) fall under the seven-year rule. However, gifts into trusts operate differently — the law classes these as Chargeable Lifetime Transfers, and they can trigger an immediate 20% IHT charge if they exceed the available nil-rate band at the time of the gift. Always check the type of transfer before assuming the seven-year rule applies.

Can I give my house to my children to avoid inheritance tax?

This is one of the most common questions in IHT planning — and the answer is: it’s complicated. If you give your house away but continue to live in it rent-free, HMRC treats this as a Gift with Reservation of Benefit, meaning the house stays inside your estate for IHT purposes regardless of who holds the legal title. To push it outside the estate, you’d need to either pay full market rent to the new owner, or genuinely vacate the property. Both options carry practical and financial consequences worth working through with an adviser. See our guide on reducing IHT on family property for more detail.

Will pensions be subject to inheritance tax?

From April 2027 (subject to final legislation), HMRC will include unspent pension funds within the estate for IHT purposes. This marks a significant shift — currently, pension pots sit entirely outside the estate. Anyone who has structured their estate assuming a large pension fund would pass tax-free needs to revisit that planning urgently. HMRC is still working through the technical detail of how this interacts with existing pension nominations, so watch for further guidance.

Is there inheritance tax between spouses or civil partners?

No. Transfers between UK-domiciled spouses and civil partners escape inheritance tax entirely — both during lifetime and on death. This exemption carries no upper limit when both parties hold UK domicile. Leaving everything to a surviving partner on first death is therefore straightforward from a tax perspective — though the estate planning still needs to look ahead to what happens when the surviving partner later dies, and whether their estate will sit within the available thresholds at that point.